Learn useState In 10 Minutes - React Hooks Explained

Learn how React components maintain and update their state, allowing you to create dynamic and interactive user interfaces.

Introduction

Modern web applications are highly interactive; users can click on buttons, fill out forms, toggle navbars, play a video, and so on.

Interactivity makes the UI, therefore the React components change as the time wheel rolls by.

When you type on an input field, the wrapper component should keep track of the last typed value.

If you toggle a navbar, it should always stay toggled and never get reset back to its previous state as long as we’ve never clicked on the toggle button again.

In other words, sometimes a React component needs some kind of local and personal memory to remember what’s needed to accomplish its mission.

This specific type of memory is called a component’s local state. It is the heartbeat of any interactive application, and it is the focus of today’s article.

To master state, we need to understand not just how to use it, but why React handles it so specifically. We will dive into:

-

Why a locally declared variable can’t serve as state for the component.

-

The useState hook: We will introduce the React way of dealing with states, explaining the intuition behind it and how to use it properly.

Why isn’t a locally declared variable enough?

Let’s say that we want to create a basic counter component that supports incrementation, decrementation, and reset operations.

Or in other words, a React component that renders a count variable while providing buttons for incrementing, decrementing, and resetting that counter.

We will declare the count variable locally using the “let” keyword and then render it in the JSX via the curly braces syntax.

function App(){

let count;

console.count("UI: Updated");

return (

<div>

<div>Count is {count}</div>

<div>

<button onClick={(e)=>{

count += 1;

console.log(count)

}}>Increment</button>

<button onClick={(e)=>{

count -= 1;

console.log(count)

}}>Decrement</button>

<button onClick={(e)=>{

count = 0;

console.log(count)

}}>Reset</button>

</div>

</div>

)

}Each button is attached to an event handler that changes the “count” variable depending on the operation.

Adding one on the incrementation, subtracting one on the decrementation, and resetting the variable to zero when the reset button is clicked.

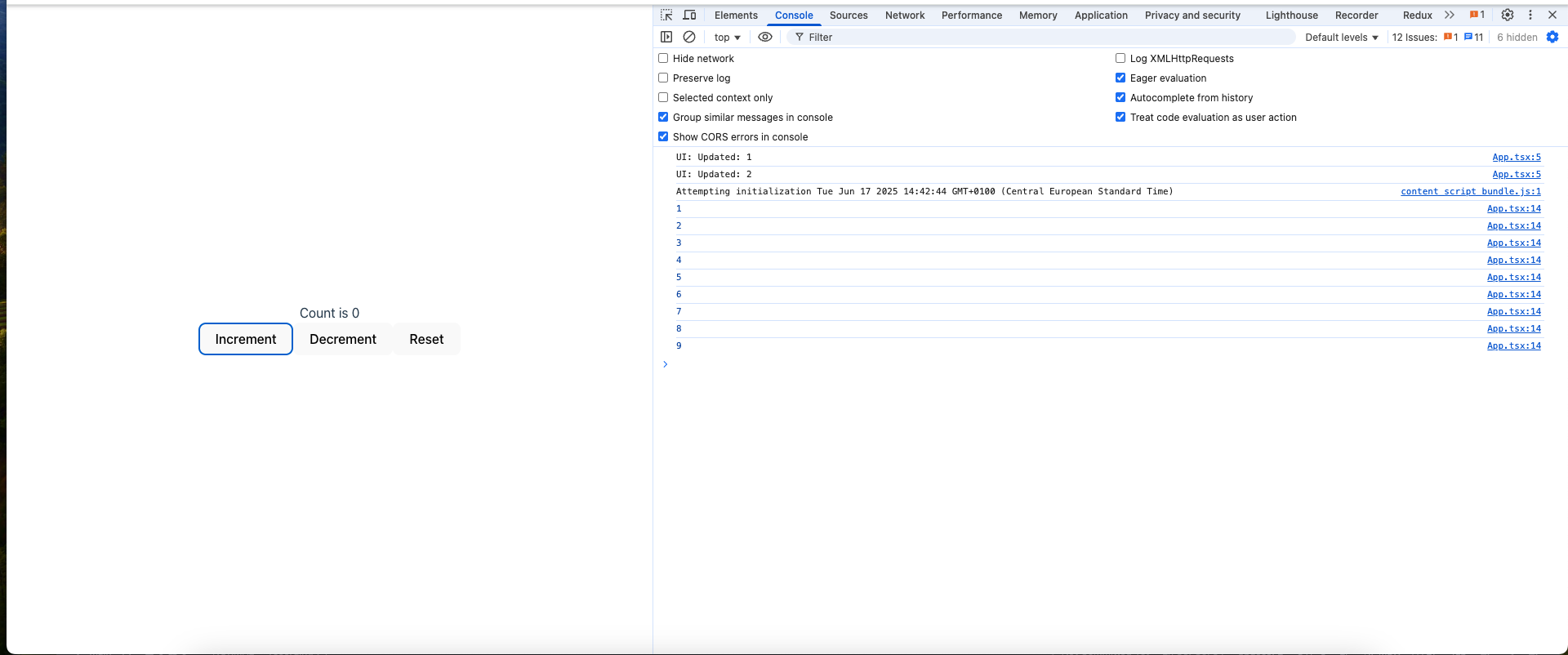

Now, let’s try to increment the “count” while checking the console logs in the inspect window in parallel.

As you can tell, the “count” variable is indeed getting incremented with every click, but the displayed “count” value in the UI is stuck at 0.

Said differently, the component is not re-rendering the JSX when we increment the variable.

Notice also that the UI: Updated message got printed two times meaning that the component have only rendered one time. Well, By default React uses Strict mode in development environment for debugging reasons, that’s why the message got printed twice. In production environment, Strict mode gets disabled, thus only 1 render will occur.

Come on, how is it even possible to call this framework React if it’s not reacting to the “count” variable changes by re-rendering the component and updating the UI?

Well, the reason behind that is that changes to the locally declared “count” variable can’t trigger a re-render. Or in other terms, no one is telling React that the “count” variable has changed.

Let’s suppose that the “count” variable is indeed triggering a re-render. Will that be enough?

Think about it; even if a re-render gets triggered, the variable will get re-declared again and reinitialized to zero.

So to summarize all that has been said, we need two built-in mechanisms to make the counter-example work:

-

Something that tells React that a given state variable has changed, therefore triggering a component’s re-render and then updating the UI.

-

And a way to persist data or state between the component’s re-renders so that our “count” variable value will never get reset or lost between re-renders again.

Fortunately, React has to react to this by providing a built-in utility function called “useState.”

Introducing “useState”: The React way of Dealing with State

import {useState} from "react"

function App(){

const stateTuple = useState()

const [state, setState] = stateTuple

}useState can be imported from “react” and used inside any component to declare a local state.

useState returns what is known as a tuple, which is just a fixed-size array.

In our case it has a fixed length of two items, the first being the state variable that persists between re-renders and the second one being a setter function, “setState,” that can be used to update the state while triggering a re-render.

To make this more convenient, we usually use the array destructuring syntax to store the two returned array items in two different variables without a lot of boilerplate code.

import {useState} from "react"

function App(){

const [state, setState] = useState()

}The items are usually named variableName followed by setVariableName, but you’re free to name them as you prefer.

Moreover, useState accepts an argument that consists of the initial value of the state; for example, in our case, we want to declare a state variable named “count” and a corresponding setter function named “setState” while ensuring that the “count” variable defaults to zero.

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)Let’s refactor the event handlers to set the “count” using the “setCount” setter function instead of mutating the variable directly.

function App(){

import {useState} from 'react';

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

console.count("UI: Updated")

return (

<div>

<div>Count is {count}</div>

<div>

<button onClick={()=>{

setCount(count+1)

}}>Increment</button>

<button onClick={()=>{

setCount(count-1)

}}>Decrement</button>

<button onClick={()=>{

setCount(0)

}}>Reset</button>

</div>

</div>

)

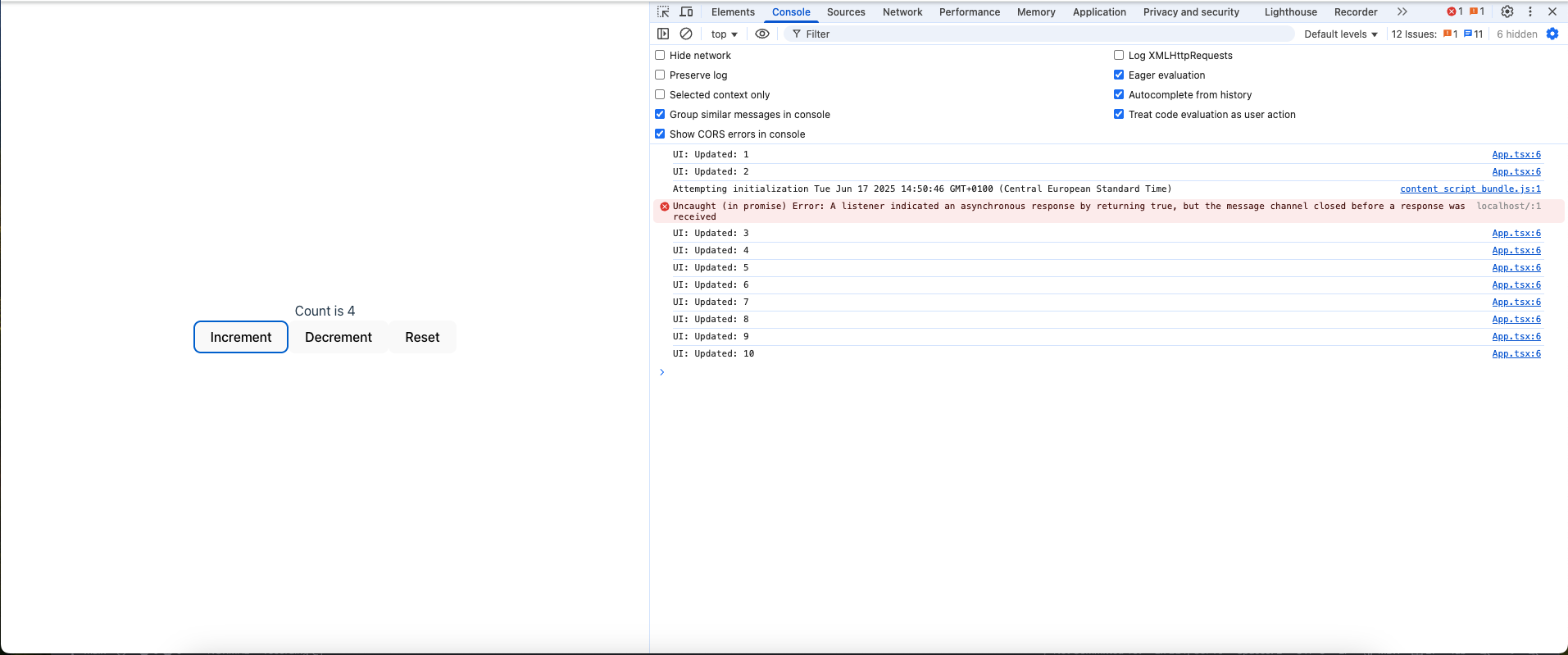

}Now, let’s try to increment, decrement, and reset the “count.”

Great! In contrast with the previous example, now the UI reacts to the count variable updates and changes whenever the count variable gets modified.

Or said differently, the component re-renders when the “count” variable gets modified with the setter function.

Even though the code inside the component re-runs entirely when re-rendering, the state still gets persisted between all the re-renders.

Hooks Rules

In React, any function starting with “use” is called a hook.

Therefore, useState is one of React’s built-in hooks.

It’s true that hooks are ordinary JavaScript functions, but you can’t use them everywhere in your JavaScript application.

Any happy marriage implies adhering to a bunch of predefined constraints, and so too does your relationship with React hooks.

First Rule

The first rule is simple yet overlooked by many developers.

You just need to make sure that you’re declaring your React hooks at the top level of the component

In other words, just after the opening curly braces ”{}” of the component’s function declaration.

That being said, don’t even think about using hooks inside loops, conditions, try/catch/finally blocks, or JSX markup.

import { useState } from "react"

function App(){

// Loops ❌

while(true){ // ❌

const [counter,setCounter] = useState(0)

}

for(let i=0;i<5;i++){ // ❌

const [counter,setCounter] = useState(0)

}

do{ // ❌

const [counter,setCounter] = useState(0)

}while(true)

}import { useState } from "react"

function App(){

if(true){ // Conditions ❌

const [counter,setCounter] = useState(0)

}

}import { useState } from "react"

function App(){

// Try Catch blocks

try{ // Try Catch, Finally blocks ❌

const [counter,setCounter] = useState(0) // Try Catch blocks ❌

}catch(error){

const [counter,setCounter] = useState(0) // Try Catch blocks ❌

}finally{

const [counter,setCounter] = useState(0) // Try Catch, Finally blocks ❌

}

}Instead always use them at the top level of your function component before any early return statement.

import {useState} from "react"

function App(){

const [counter,setCounter] = useState(0) // ✅

if(true){ // Early return

return null

}

const [counter,setCounter] = useState(0) // ❌

}Usually, React will let you know when you’ve broken one of these rules with a detailed error message.

Second Rule

The second rule is non-negotiable: Hooks belong exclusively inside React function components.

Can we use hooks inside normal functions, classes, or objects? Well, it depends on if you want to see your app crashing on your face or not.

You might wonder, “Can I just sneak a hook into a regular JavaScript function or a class?” Well, it depends on whether or not you want your app to blow up in your face

Hooks aren’t designed to work with ordinary functions; their goal is to hook into React internals to give you total control over the components.

import {useState} from "react"

function App(){

const [counter,setCounter] = useState(0) // ✅

}

function add(a,b){

const [counter,setCounter] = useState(0) // ❌

return a + b;

}

class Counter{

const [counter,setCounter] = useState(0) // ❌

}

const calculator = {

add:(a,b)=>{

const [counter,setCounter] = useState(0) // ❌

}

}How State Updates Work

Now that we’ve discussed the rules for having a happy relationship with React hooks**,** let’s get back to our previous counter-example and break down what’s happening under the hood.

When we click on the increment button, the click event gets fired; therefore, the event handler will start running.

Inside the event handler’s code, the “setCount” function gets called with the current count state value, which is equal to zero plus one, as an argument.

setCount(count + 1) // count=0Calling the latter triggers a second re-render or tells React, “Hey, some state got updated here; please re-render the component and then update the UI.”

Even though the “setCount” function executes on the current render, the “count” state value will remain equal to 0 until the next render.

function App(){

// First Render

//...code

// count = 0

return (

<div>

<div>Count is {count} {/* 0 */}</div>

<div>

<button onClick={()=>{

setCount(count+1) // setCount(0+1)

// count = 0 , It's scheduled to change on the Second render

}}>Increment</button>

{/** ... code */}

</div>

</div>

)

}In other terms, React queues all the updates of the current render in memory until the next render happens, where the UI will get constructed depending on the new state value.

On the second render, the “count” state will be incremented; therefore, it will be equal to 1, the component will execute from top to bottom, return the JSX with the updated count state value, and finally React will update the real DOM in the user’s browser.

function App(){

// Second Render

//...code

// count = 1

return (

<div>

<div>Count is {counter} {/* 1 */}</div>

<div>

<button onClick={()=>{

setCount(count+1) // setCount(1+1)

// count = 1 , It's scheduled to change on the Third render

}}>Increment</button>

{/** ... code */}

</div>

</div>

)

}Multiple Components and State

Let me ask you a question now. What would you expect if we had called the Counter component two times in the App component? What would happen if we incremented one of them?

function Counter(){

/*Previous counter code*/

}

function App(){

return(

<div>

<Counter/> {/* count = 1*/}

<Counter/> {/* count = 0 */}

</div>

)

}As we have said, from the beginning the state is private and personal. So incrementing the first counter will only affect the first called component.

Multiple State Variables

Another question that may traverse your mind is, can we use more than one state in a React component?

The answer is absolutely yes, we can do that.

Let’s take this “Greeting” component as an example.

function UserGreeting() {

const [name, setName] = useState('Guest');

const [showGreeting, setShowGreeting] = useState(true);

return (

<div>

{showGreeting && <p>Hello, {name}!</p>}

<button onClick={() => setName(name === 'Guest' ? 'User' : 'Guest')}>

Toggle Name

</button>

<button onClick={() => setShowGreeting(!showGreeting)}>

{showGreeting ? 'Hide' : 'Show'} Greeting

</button>

</div>

);

}Here we are declaring two pieces of state: one holding the name, which can be either “Guest” or “User,” and the other one is a boolean named “isGuest” controlling whether to show the greeting message or not.

const [name, setName] = useState('Guest');

const [showGreeting, setShowGreeting] = useState(true);The component conditionally renders a greeting message at the top along with two action buttons at the bottom.

- The greeting message is only shown when the “showGreeting” state is set to “true.” The message consists of a “p” tag wrapping a “Hello” string and the current name state value.

{showGreeting && <p>Hello, {name}!</p>}- The first action button is responsible for toggling the name state between “Guest” and “User.”

<button onClick={() => setName(name === 'Guest' ? 'User' : 'Guest')}>

Toggle Name

</button>- The second one toggles the “showGreeting” state between true and false.

<button onClick={() => setShowGreeting(!showGreeting)}>

{showGreeting ? 'Hide' : 'Show'} Greeting

</button>React is smart enough to determine which state variable corresponds to which “useState” call as long as you follow the law of hooks.

React is internally relying on the order of useState calls.

With all that being said, we can conclude that using two states or more is a completely viable and easily achievable option in React as long as we respect the law of hooks. Because React is internally relying on the order of useState calls to distinguish between the different states.

Conclusion

Without state, our application becomes just a boring website with no interactivity. In other words, the building blocks that constitute our UI will never change after the first render without the notion of state.

It’s true that we’ve gone through the intricacies of “useState”—starting from the intuition behind it and the law of hooks, to how and why a component can have multiple private states, and finally, how it all works.

But we’ve just scratched the surface of useState. There are many other intricacies that we haven’t mentioned yet—the kind of things that can save you hours of debugging.

In the next article, we will be diving deeper into how React goes from rendering to displaying the UI on the user’s browser screen.

Thank you for your attentive reading and happy coding!